Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., The Common Law

- October 20th, 2021

- by specialcollections

- in Collections, Recent Acquisitions

The following is another post derived from the Bounds Law Library’s recently acquired A.S. Williams III Collection.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr, The Common Law (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1881). This is a first edition of this famous treatise. It is bound in dull red buckram, in excellent condition; the corners are essentially unbumped. The front pastedown endsheet has a bookplate of Robert B. Nason, an arte nouveau design of a woman standing in front of a crescent moon with a shield bearing the Harvard motto, “Veritas.”

The recto of the front free endsheet has a sticker, lower left, for “G.A. Jackson Law Books, 8 Pemberton Square Boston, Mass.” Also on this recto, penciled notes: “1st ed. of important Legal Treatise $450.00” followed by “28-6-1910.” No marks inside the text.

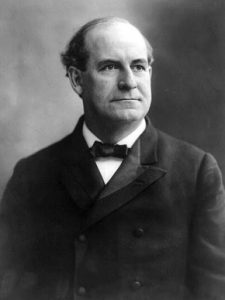

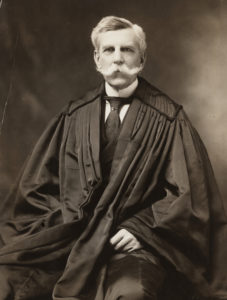

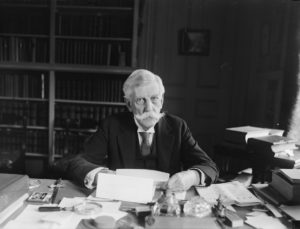

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. (1841-1935) is one of our most famous Supreme Court justices.  He served on the high court from 1902-1932, and secured renown as a defender of free speech; see his dissent in Abrams v. United States (250 U.S. 616, (1919). Holmes was likewise willing to allow states considerable leeway in their regulation of economic interests and public welfare.[1] Long-lived, handsome, and quotable by the yard, Holmes was for many people the very model of a Supreme Court justice. He is much less well-known as a legal scholar, having written only one original book, The Common Law.[2] But that one book, published when he was forty, has been to the study of jurisprudence what his opinions were to the evolution of case law.

He served on the high court from 1902-1932, and secured renown as a defender of free speech; see his dissent in Abrams v. United States (250 U.S. 616, (1919). Holmes was likewise willing to allow states considerable leeway in their regulation of economic interests and public welfare.[1] Long-lived, handsome, and quotable by the yard, Holmes was for many people the very model of a Supreme Court justice. He is much less well-known as a legal scholar, having written only one original book, The Common Law.[2] But that one book, published when he was forty, has been to the study of jurisprudence what his opinions were to the evolution of case law.

The first page of Holmes’ treatise contains a line that has gone ringing down the years: “The life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience.” The rest of The Common Law contained Holmes’ brilliant if difficult historical treatments of crime, torts, property and contracts, all of which tend to show that the evolution of law has been in response to the pressures exerted by human beliefs, desires, and doings. But that one line was memorable and utterly revolutionary. For centuries—certainly since the decisions of the seventeenth-century jurist, parliamentarian and treatise-writer Edward Coke—learned lawyers had spoken of the law as a “science of reason,” a system of logic that has, from time to time, become entangled in scholars’ perceptions of Natural Law—law as derived from the law of God. Under this system, jurists applied their logical tools, mindful of the authority of precedents, and “discovered” what the law had to say. Holmes was having nothing to do with the circular logic of such Formalism. Rather he asserted, by implication and directly, that “judges make law.”[3]

Indeed, The Common Law applied the philosophical principles associated with Pragmatism, and brought them into use within the halls of the legal academy; he also invited them to sit with him on the Bench. His writings and jurisprudence combined were precursors of what is known as Legal Realism, described by Judge Richard Posner as “the most influential school of twentieth-century American legal thought and practice.” In his book The Essential Holmes, Posner notes Holmes’ early exposure to the writings of English thinkers such as John Stuart Mill and James Fitzjames Stephen. He then declares that their ideas, operating through Holmes, “helped to make American thought more cosmopolitan and (paradoxically) to liberate American jurisprudential thought from slavish adherence to English models.”[4] And to think—Holmes had written The Common Law before he ever sat as a judge!

Holmes’ biographers have made their bows to The Common Law. Liva Baker’s The Justice from Beacon Hill devoted a chapter to it, asserting that Holmes had “given the law a vitality it never before had possessed.”[5] More recently Stephen Budiansky has written that The Common Law was a “work of profound learning, and revolutionary, even shocking implications.”[6]

The magisterial Mark DeWolfe Howe, on the other hand, viewed The Common Law as a very successful tour-de-force. He admits that it “was something far more important than a compendium of insights.” But as he considered Holmes’ transition from practitioner to Harvard law professor to judge of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts— all of which he accomplished in two years’ time, from 1881 to 1882—Howe concluded that “other traits of intellect and character than those which gave that book its power would have been called upon to produce a systematic work on legal history or legal philosophy.”

It may be worth noting that the status of Holmes’ treatise has been confirmed by the recent publication of Steven Alan Childress’ Annotated Common Law (New Orleans: Quid Pro Law Books, 2010). If great books initiate conversations—between readers, between authors and readers, between generations—The Common Law has “been in that number” for a long time.

PMP

[1] For the negative side of Holmes’ willingness to let states control public policy without interference on the grounds of “due process,” see Holmes’ opinion in Buck v. Bell (274 U.S. 200, 1927) , in which he upheld Virginia’s mandatory sterilization of the “unfit.”

[2] Holmes’ speeches and essays were also published. See Holmes, Collected Legal Papers (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Co., 1921).

[3] Holmes’ comment on judge-made law is quoted in Stephen Budiansky, Oliver Wendell Holmes: A Life in War, Law, and Ideas (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2019), 177.

[4] Richard A. Posner, editor, The Essential Holmes: Selections from the Letters, Speeches, Judicial Opinions . . . (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), xi, xx.

[5] Liva Baker, The Justice from Beacon Hill: The Life and Times of Oliver Wendell Holmes (New York: Harper Collins, 1991), 246-270, quoted passage at 258.

[6] Budiansky, op. cit., 10.

[7] Mark DeWolfe Howe, Justice Holmes: The Proving Years, 1870-1882 (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1963), 280-283, quoted passages on 282.

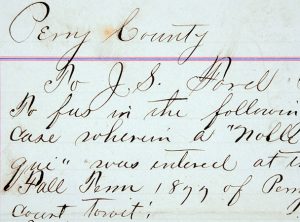

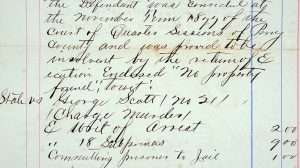

One such document describes the court’s charge of twelve dollars and eighty cents for services provided in administrating a burglary charge. In this case, ten cents per mile was billed to the defendant for guard services required during his incarceration. Similarly-rich detail is provided for other court decisions, including conviction-related fees for the quasi-anachronistic charge of “carrying concealed brass knuckles.”

One such document describes the court’s charge of twelve dollars and eighty cents for services provided in administrating a burglary charge. In this case, ten cents per mile was billed to the defendant for guard services required during his incarceration. Similarly-rich detail is provided for other court decisions, including conviction-related fees for the quasi-anachronistic charge of “carrying concealed brass knuckles.”